Many well-meaning people have lauded the creation of a human rights museum in Winnipeg by the Canadian Media Giant, Global, which controls most news outlets in Canada, and exercises strict control over the content we receive, as dictated by the decidedly pro-Israel directors.

EXCLUSIVE: The article the National Post refused to run.

The Idea of a Canadian Museum of Human Rights By Amos Friedland

On March 17, a review committee will choose eight semi-finalists to compete in an architectural competition to build The Canadian Museum for Human Rights, the brainchild of the late Dr. Israel Asper, to be constructed in Winnipeg. Thirty architects selected from an initial list of some 500 firms from around the world, are now working on their submissions. Included on this list are “starchitects” Frank Gehry, Daniel Libeskind, Zaha Hadid. The list also includes many well know Canadian architects like Moshe Safdie and Douglas Cardinal, as well as some of the country’s youngest and most promising talent. The finalist chosen to build the museum will be announced July 1, 2004 – Canada Day.

The museum will be the largest monument to human rights in Canada – and the world. It will be built on the scale of such world class museums as the soon to be opened Holocaust History Museum at Yad Vashem Museum in Jerusalem, the Jewish Museum in Berlin, and the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. Yet instead of commemorating a specific event, the Canadian Museum’s focus will be on human rights in general – with an emphasis on Canada’s role in the human rights arena. Rumor has it the museum will be named after Pierre Trudeau.

The $270 million museum is being financed with a combination of public and private money (70% / 30%). The latter is both guaranteed and solicited by the Asper Foundation. Some 30-50 corporate donors, chosen by the Asper Foundation, will donate one million dollars or more. They will then be named “Friends of the Museum,” with considerable control in the direction of future affairs, programming, naming, and other museum decisions; each individual’s influence will be determined on a pro-rata basis of how much money he or she has contributed.

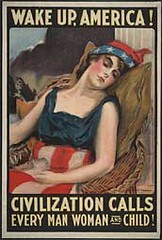

The premises of the museum, outlined in the proposal given to the competing architects, calls for “zones,” through which the visitor must pass: (1) a Holocaust zone; (2) an international abuses / responses zone; (3) a Canadian abuses zone; and, (4) a Canadian achievement zone. Additionally, there is to be a “garden of contemplation” and a “tower of hope,” where visitors will literally “make the light of justice burn brighter” by pressing a touch-sensitive “commitment panel” connected to a Torch of Justice. Along the way, there will also be a “Hall of Fame / Walk of Shame,” foregrounding the greatest champions and the worst abusers of human rights. The explicit theme of the museum is to be “light versus dark.” The museum will also serve to educate teenagers, police officers, the Canadian military, and others.

Yet if a human rights museum worthy of the name is to be built, and if it is to inspire genuine and not merely self-congratulatory reflection on the part of Canadians, must it not move beyond these simplistic premises on which it is currently based? Human rights issues are not always black-and-white, and are often not amenable to a simplistic reduction of “the forces of good” and the “forces of evil.” It is true that there are gradations in evil; but while it is disingenuous to pretend that the culpability of all is the same, it is no less disingenuous (and dangerous) to portray these complex issues of human rights as stark points of contrast between the light and the dark. Otherwise, there is a great risk that we will end up building a stagnant monument: a flattened symbol that shows where our thinking leaves off, and where complacency and self-satisfaction begins.

If this museum is to be a great work of architecture, then it must take shape as a living space that challenges both the physical and intellectual spirit of the Canadian people. It must avoid simplistic reductions, yet be capable of inciting thoughtful judgement and timely action. In this respect, the Canadian Museum should be more akin to the spirit of such processes as the Truth and Reconciliation Committee in South Africa, than any static commemoration of past events. It will of course recall these past abuses, but human rights represent an unfinished project, with ever new abuses to confront. The building itself must be capable of embodying the immense complexities that this idea of human rights carries with it; it must provoke us to thought, not reassure us with the banality of a good versus evil rhetoric. The architecture for the new museum must move beyond the spatial simplicity that is now proposed. It must come to terms with the fact that in reality the borderlines of this subject are far more permeable than we might suppose.

Clear distinctions can be difficult to draw for the Hall of Fame, and Walk of Shame. For instance, Winston Churchill, a champion of human rights and liberty, in his fight against Hitler, nevertheless maintained strict immigration limits for Jews throughout the war, for both England and Palestine. He refused an offer to ransom one million Jews in 1942, after the scale of the “Final Solution” was becoming known, in part because there would be “no place to put them” – leading (Nazi arch-criminal) Eichmann to declare that “there was no place on earth that would have been ready to accept the Jews, not even this one million.” Many Jews could have escaped extermination had most nations stretched their immigration quotas, Canada included. It’s easy to pass judgement on this at such a remove, and in retrospect. But ten years ago, where would eight hundred thousand Tutsi Rwandan refugees, faced with imminent execution, have been welcomed? Where, today, are AIDS orphans and endangered refugees from conflict zones such as the Congo and Liberia welcomed en masse? The difficulties of such political decisions often involve necessary compromises, the choice between the “lesser of two evils.” Such decisions are not black and white, even if the various shades of gray are nevertheless far from uniform.

What of Nelson Mandela, whom the Museum proposes to honour? Surely we cannot question his place in the “Hall of Fame”? However, Mandela fought against Apartheid in South Africa through means that included violence, and he was branded a terrorist by his own nation and the United States, and convicted for sabotage and conspiracy to overthrow the government. Later, Mandela would himself declare that “nonviolence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon…At a certain point, one can only fight fire with fire.” It is a similar nuance of political judgement that is as required regarding the case of a Mandela as with a Churchill: the fight against Apartheid was indeed a “long walk to freedom,” an overcoming of a historical evil; yet it was not accomplished (or accomplishable) through the non-violent tactics of Martin Luther King or Mahatma Gandhi. Innocent people on both sides of the struggle were killed, tortured, and violated. These violations remain violations; but they co-exist with the historical achievement that the elimination of Apartheid brought.

One of the Museum’s first temporary exhibits will focus on terrorism. Terrorism seems to offer the most horrendous human rights violations of our day (the clearest case of the “forces of darkness,” which the image of the destroyed towers of the World Trade Center serves to depict), as our new Justice Minister Irwin Cotler has strongly claimed. Yet the “war on terrorism” is often itself used to justify human rights abuses. In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Russia, China, and Israel were quick to voice unconditional support for the United States – with whom they share a common enemy: “the terrorist,” against which even the worst human rights abuses are justified. Since then, Russia’s bloody war against the Chechnya and China’s brutal occupation of Tibet, both justified using anti-terrorist rhetoric, have been largely overlooked by Americans. While on trial for genocide in Kosovo and Bosnian, Slobodan Milosevic has stated that he, too, was fighting terrorism (where indeed Al-Qaeda operatives were at work against him).This last allusion points to a greater issue: how do we, and how will the museum, situate those engaging in conflicts today, especially when the political implications of doing so are so high? How do we classify the Palestinian teenage girl, who walks into a crowded Jerusalem restaurant and blows herself up, killing a maximum number of Israeli civilians? As an outrageous violator, bent on the genocidal elimination of the Jewish people; or as a martyr of liberation, struggling to emancipate her people from destitution and Apartheid-like conditions? What of the young Israeli Defense Force private who courageously risks his life guarding fellow citizens from terrorist attack, yet contributes to the occupation and degradation of another people in doing so? Each represents a struggle for justice; yet each also commits violations and abuses of the other’s basic human rights.

Will this nuance be preserved in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, under the direction of the Asper Foundation-led “Friends of the Museum”? The aggressive manner in which the late Israel Asper controlled the content of editorials and articles in his newspapers, demanding an unequivocal support of the state of Israel and its actions in its “battle against terrorism,” as well as statements he made, such as, “I think Canadians should show solidarity with a very beleaguered people. Israel is the only democracy in the entire region. It supports human rights. . . . They must be supported,” do not portend well for any neutrality or nuance; nor does the great control that the corporate “Friends of the Museum” – solicited and selected by the Asper Foundation – will hereinafter have over the direction and running of the museum.Finally, it is ironic, especially for the Québecois, that of all Pierre Trudeau’s utterances, the museum has chosen for its motto: “The only passion which should move us at this moment is a passion for justice. Through justice, we shall defend our values, our order and our laws. Through justice, we shall rid ourselves of terrorism and perversion. Through justice, we shall recover our peace and our liberty.” These are the very words he spoke when he declared martial law in 1970 in Quebec, when citizens rights were suspended, and masses of Canadian troops took over the streets of Montreal and Quebec, arresting hundreds, and holding hundreds without due process. This decision may have been a justified one (perhaps it was justified in principle, but still excessively deployed, using faulty intelligence on the threat the nation was facing). Be this as it may, it is probably a mistake to isolate this moment as representative of Trudeau’s long campaign for human rights, which included the achievement of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Quest for a Just Society, and others. Especially, it should not be isolated and stripped of its context, just because such isolation serves the purpose of finding a convenient “sound bite” against terrorism. Trudeau himself recognized the gravity of his invocation, which, though taken in defense of a democracy under attack, nevertheless “suspend[ed] the operation of the Canadian Bill of Rights,” temporarily. At the very moment he invoked the War Measures Act, he had this to say to Canadians as well: “To those of you who find these measures distasteful, I can only sympathize and applaud their speaking out against them . . .” Perhaps these last words would serve as a better motto for the struggle for human rights.

Today, two and a half years after 9/11, it may indeed be the case that our own security is achieved only at the expense of such measures as the U. S. Patriot Act, continual imprisonment of “enemy combatants” at Guantanamo Bay and on brigs at sea, and practices such as the deportation of Canadian citizens to Syria for the purposes of torture and information extraction. Prominent legal celebrity Alan Dershowitz has even suggested that special “torture warrants” be incorporated into American law to “safeguard our liberty.” We do not have the benefit of hindsight here; so our positioning cannot be as secure as Trudeau’s was when, much later, he reflected on his decision to invoke the War Measures Act and judged it to be correct in principle, but perhaps too excessive and broadly sweeping in its application. Yet, though we do not have this hindsight – the future is still to come – we would be remiss in not questioning and interrogating these responses of the American government, as Trudeau himself commended citizens for doing at the very moment of the October Crisis.

“The blood that’s on everyone’s hands . . . that flows and has always flowed through the world like a waterfall, that is poured like champagne and for the sake of which men are crowned in the Capitol and then called the benefactors of mankind.” These words, from Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, serve as strong words of caution for us. Clearly, there are degrees of culpability – I, for example, am not Saddam Hussein. Yet none of us stands outside either. There is blood on everyone’s hands. The museum’s demarcated zones are easily blurred; we cannot just retreat into gardens of contemplation from complex scenes in which we are implicitly implicated, nor finally should we ascend above it all into a tower of hope (on the contrary, hope must be joined with struggle, in a real recognition of ourselves in the zones). There are extreme exemplars who could perhaps be put on one side or the other – Gandhi or Martin Luther King on the one, Hitler or Pol Pot on the other – but in most cases there is a high degree of permeability between the two which we do not benefit from ignoring (as the examples of Mandela, Churchill, and Trudeau demonstrate). To point out this permeability neither denies the accomplishments of these figures, nor precludes the difficult but necessary political task of judging between degrees of evil or atrocity. But it does call into question the imagery of the dark versus the light that undergirds the proposed vision of the museum, and that plays itself out in the premises of construction given to the architects.

It is to just this permeability that the architecture which comes to define the singular institution of the Canadian Museum of Human Rights must respond. Such a museum will only become more than an empty symbol if it is committed to exploring all of the complexities of the history of human rights – past, present, and future – not only touting the manifestly obvious facts situated at a reassuring distance from us. This exploration must begin with the architects of the museum, and continue with the activity of curators and finally be passed on to the visitors. This is how a building, a public space, takes on a life of its own. It will rise to the challenge that such a formidable and commendable endeavor undertakes only if it itself challenges the comfortable and comforting premises upon which the museum is currently based. Challenging these premises, it will also challenge us – as Canadians, perhaps also as world citizens – to respond to the challenge of human rights that can, today, know of no complacency and no easy comfort.

We await the architects of such a museum.